News Article

Sun Spray

Irish researchers developing solar cells to be sprayed on almost anything

Science and Technology Research Partners (STREP), a Dublin based company, is attempting to develop 'spray-on' solar cells which could revolutionise the use of this green technology. Energy producing solar cells could simply be painted onto a roof and, if integrated into the plastics used to build consumer electronics, these could produce their own electricity.

Dr. Mazhar Bari is behind the research taking place in his company, (STREP). The goal is to produce much cheaper solar cells based on titanium dioxide and other nanomaterials, while avoiding the conventional silicon based devices, says the University College Dublin and Cambridge University graduate.

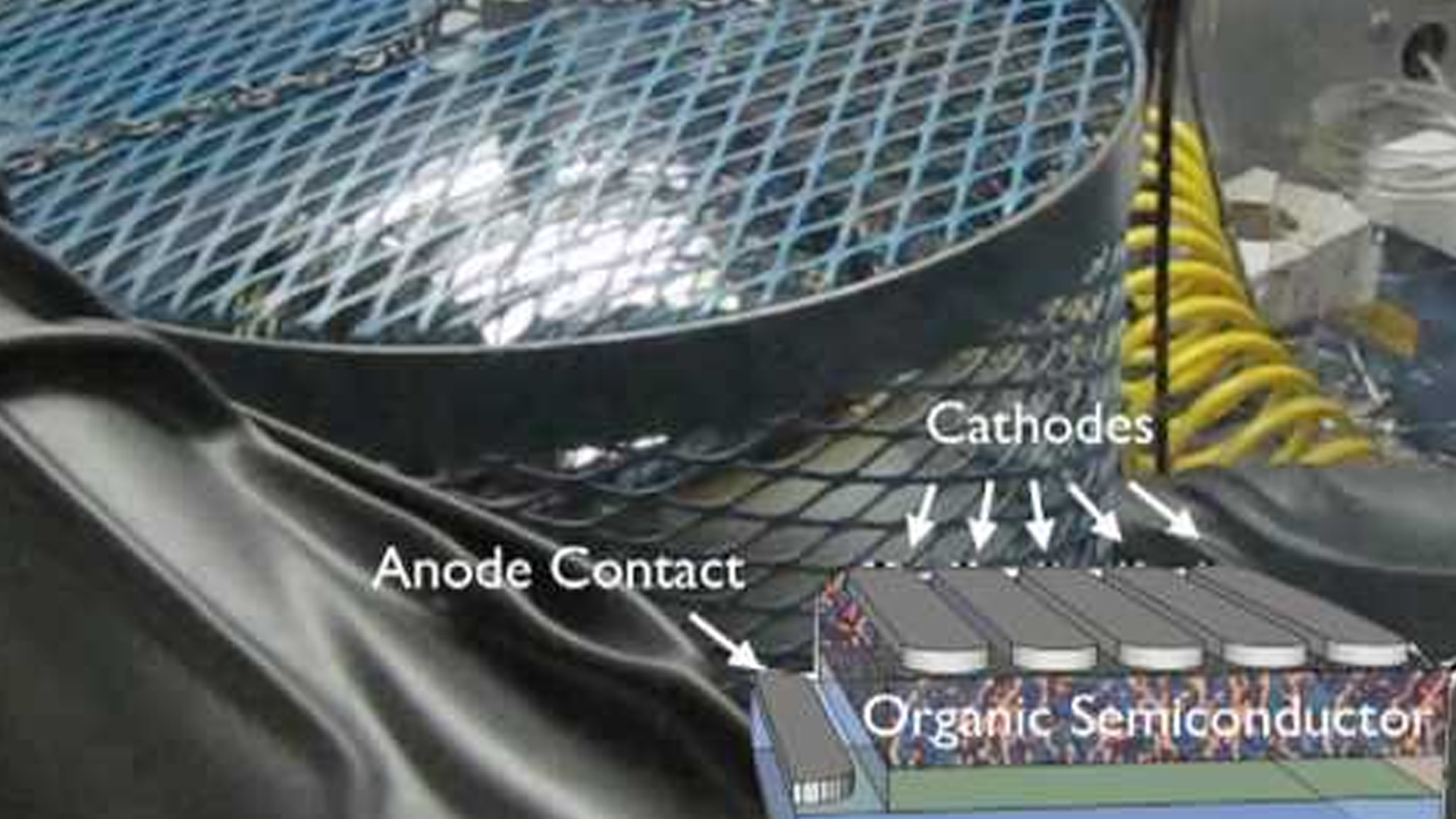

The work relates to developments in so called third generation solar cell devices. The original solar cells from the 1970s were crystalline silicon on glass. They were difficult to manufacture and costly, he says.

These were replaced in the 1980s by thin film silicon based solar cells and these in turn have been replaced by 'wet' cells that use photo active dyes, conducting polymers and nanoparticles to produce electricity.

"The technology in its current stage is a wet state. What I am doing is working on the solid state version. It is wet chemistry basically but I have found a way to make it solid state." Bari says. "Right now, it is more screen printing but it will develop at some stage into a sprayable technology. It will be applied very much like paint."

The efficiency of solar cells relates to the percentage of solar energy successfully converted into electrical energy. The dye sensitised solar cells being developed by Dr Bari are only about 40 per cent as efficient as the best silicon cells, but they are significantly cheaper and simpler to produce. Dr Bari's goal is to achieve a 10 per cent conversion rate at 10 per cent of the cost of traditional solar cells. His thin film cells would be flexible, something that would really change the way solar cells are used, he says.

They could be painted onto metal roofing sheets to deliver reasonable amounts of clean solar electricity. They could be used to power novel new electronic signage and could support a whole new range of consumer electronics products.

"If you built it into the fabric of consumer devices, it could provide electricity." This approach would probably be insufficient to fully power a laptop or a mobile phone but it could provide supplementary power to extend battery life. Its low cost also suggests the technology has great potential for electricity production in sun rich developing countries.

Dr. Mazhar Bari is behind the research taking place in his company, (STREP). The goal is to produce much cheaper solar cells based on titanium dioxide and other nanomaterials, while avoiding the conventional silicon based devices, says the University College Dublin and Cambridge University graduate.

The work relates to developments in so called third generation solar cell devices. The original solar cells from the 1970s were crystalline silicon on glass. They were difficult to manufacture and costly, he says.

These were replaced in the 1980s by thin film silicon based solar cells and these in turn have been replaced by 'wet' cells that use photo active dyes, conducting polymers and nanoparticles to produce electricity.

"The technology in its current stage is a wet state. What I am doing is working on the solid state version. It is wet chemistry basically but I have found a way to make it solid state." Bari says. "Right now, it is more screen printing but it will develop at some stage into a sprayable technology. It will be applied very much like paint."

The efficiency of solar cells relates to the percentage of solar energy successfully converted into electrical energy. The dye sensitised solar cells being developed by Dr Bari are only about 40 per cent as efficient as the best silicon cells, but they are significantly cheaper and simpler to produce. Dr Bari's goal is to achieve a 10 per cent conversion rate at 10 per cent of the cost of traditional solar cells. His thin film cells would be flexible, something that would really change the way solar cells are used, he says.

They could be painted onto metal roofing sheets to deliver reasonable amounts of clean solar electricity. They could be used to power novel new electronic signage and could support a whole new range of consumer electronics products.

"If you built it into the fabric of consumer devices, it could provide electricity." This approach would probably be insufficient to fully power a laptop or a mobile phone but it could provide supplementary power to extend battery life. Its low cost also suggests the technology has great potential for electricity production in sun rich developing countries.