Photovoltaics and IP: The calm before the storm?

The investment of time in photovoltaics research is reflected by the intellectual property generated in the field. To date, over 180,000 patent applications relating to solar power have been filed worldwide; at a rate that has been rapidly increasing since the turn of the millennium. Filtering down these filings to those directly related to the design of photovoltaic (PV) cells, rather than their application, we were able to analyse a representative sample of these filings. Figure 1 shows that the patent application rate (normalised for the overall increase in patent applications) and worldwide PV capacity have followed similar trajectories since 1998.

Though Japan has dominated the photovoltaics scene, in terms of patent filings, for most of the industry's history (Figure 2), the post-Kyoto (Dec '97) years have seen a surge in applications being filed in China, the US, Korea, and Taiwan; with the US and China overtaking Japan during the last decade. This is not reflected however by the relevant market sizes (Figure 3); with Germany having the greatest PV capacity by some margin (as of 2010).

![]()

Figure 1

![]()

Figure 2

![]()

Figure 3

Where the distribution of patent filing is reflected however is in the trends in manufacturing. In 2004 Japan produced just over 50% of the world's photovoltaics (by MW), but within 6 years this dropped to less than 10%, as the Chinese solar industry swung into action. It would seem therefore, that a long history of R&D in the PV sector does not necessarily correspond to commercial success in the current market.

This can also be seen when looking at the assignees of solar cell patents. The 20 assignees with the most patents in our focused PV cell search are shown in Figure 5; in comparison, the top 10 solar module suppliers in 2011 (by market share) are listed in Figure 6, along with the number of solar related patents they hold (using a much broader keyword search). Comparison shows that of the top 20 assignees in Figure 5, only Sharp and First Solar appear in the top 10 manufacturers "“ although it should be noted that companies such as DuPont do supply some of the top manufacturers.

![]()

Figure 5

![]()

Figure 6

In fact, some of these companies hold a remarkably small number of patents given their size, and it is clear from Figure 7, that the significant proportion of these patents are held in China. This is understandable given China's dominance in manufacture, but could leave companies such as Yingli, Trina, Jinko and LDK, who hold almost all of their patents in China, exposed when exporting their products.

![]()

Figure 7

Given this apparent disconnect between the prosperity of certain companies and their patent portfolios, it is perhaps unsurprising that there has been very little litigation in the industry, and the cases that have arisen have tended to focus on enabling technology such as interconnection and mounting devices. One such case was Westinghouse vs. Zep Solar. Westinghouse claimed infringement of two of their US patents for their "˜plug and play' installation design by Zep. Zep filed a similar case against Westinghouse in 2011 and the companies settled out of court in May 2012.

Another such case was Sunlink vs Sunpower, 2008. Interestingly the Westinghouse vs. Zep Solar case revealed that Chinese companies are attempting to (or have been forced to) strengthen their IP position by licensing technology from other firms with Trina Solar, Yingli and Canadian Solar all being revealed as licensees of Zep or Westinghouse. The desire of Chinese companies to strengthen their patent portfolios was also in evidence when the US Department of Energy used the Bayh-Dole act to block the sale of key patents belonging to the bankrupt US PV companies Evergreen Solar and Solyndra to said Chinese companies, on the grounds that the patents were based on state funded research.

The lack of litigation in the industry is an indicator of the maturity of the technology in use. With the exception of First Solar, who produce thin film CdTe cells, all the top manufacturers focus on traditional silicon solar cells. As a mature technology, improvements being made are incremental and a lot of the key patents in this technology have expired.

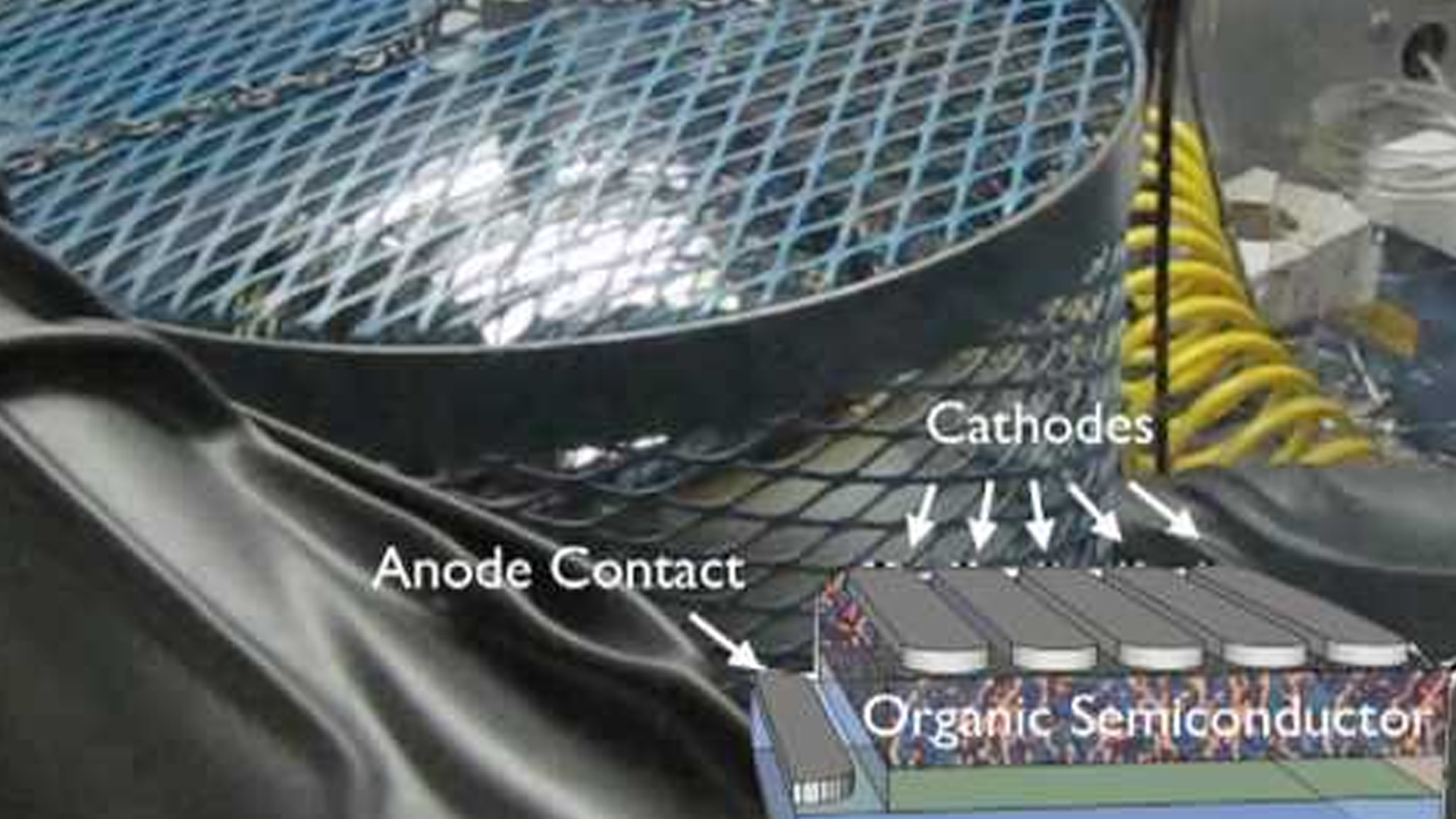

Figure 8 shows that the majority of recent patenting activity in the industry concerns second generation technologies, such as such as organic solar cells, which promise much for the future in terms of flexibility and cost to manufacture, but are not yet commercially viable due to issues with degradation and efficiency. One might expect that when this second generation enters the market, an increase in litigation will be seen, as has been the case in other technology areas such as the smartphone market.

![]()

Figure 8

The maturity of the technology has resulted in a commoditised market, in which consumers largely make choices based on the price of the product. As such, the market is greatly affected by external economic factors.As previously mentioned, China overtook Japan as the world's largest PV producer in 2008. There were a number of reasons for this shift in power: in 2005, the Chinese government identified solar power as a strategic emerging industry, making grants and low cost loans available to manufacturers; at the same time, the US and European governments triggered a surge in demand by beginning to offer subsidies and feed-in tariffs to encourage solar panel installation, in a bid to increase the uptake of renewable energy sources. China's ability to quickly build large manufacturing facilities and scale up manufacturing processes allowed them to simultaneously match this new demand and dramatically reduce the cost of manufacture. The Chinese government has also been raising its investment in scientific research institutions by 23% annually since 2001, and offering incentives for publications and patent applications - contributing to the sharp increase in Chinese patent applications seen in Figure 2.

Further evidence of the impact of economic incentives can be seen with reference to Figure 3. In 2006, the Spanish government introduced a generous feed-in tariff which resulted in a sharp rise in installations; however, the cost to the government was unsustainable and the tariff had to be cut, causing the number of installations to plummet. The gold rush the tariff had triggered meant that a lot of new companies had entered the field but often with limited expertise, resulting in many installations being poorly chosen and engineered, and consequently, unable to be maintained in the long term. In contrast, Germany's feed-in tariffs have been maintained and their renewable energy market has gone from strength to strength, despite a lack of significant technological advance over the same timescale. Over a particularly sunny summer weekend in 2012, German photovoltaics produced 50% of the country's electricity.

This dependence on external economic factors clearly has its downsides as well as benefits and the meteoric growth of the industry has proved to be unsustainable, with several US solar companies going bankrupt in 2011 and even the Chinese bubble seemingly about to burst. Following a petition led by Solarworld, against what it perceived as the dumping of cheap polysilicon in the US by Chinese companies at below market value, the US Department of Commerce confirmed in November 2012 that it is levying a tax of 14.78% to 15.97% on imports of panels and key components from China. Similar investigations are now being undertaken in the EU and India. Factors, including this dispute, alongside the financial crisis hitting exports to Europe, an oversupply in China following their government stimulus, and falling natural gas prices, have combined to see the top PV companies reporting huge losses in the first quarter of 2012. The combined debt of China's top 10 solar companies was recently estimated at US$17.5 billion. Naturally though, the Chinese government has moved to bail out struggling Chinese firms and has committed to a substantial increase in domestic installations to boost sales.

We can see that huge amounts of investment have been made in developing photovoltaic technologies and patenting these developments. Despite this, IP has not really had a great role to play in shaping the industry we see today. The solar energy market, as it stands, is largely a commoditised one, where the companies who can produce the cheapest products, not necessarily those with the strongest IP positions, are the ones that prosper. Economic policies such as government feed-in tariffs and import duties have had a far greater effect on the market behaviour than any activity involving the enforcement of patent rights.

The recent financial difficulties experienced by the industry demonstrate that it is not yet ready to stand on its own two feet, without the support of governments keen to promote renewable energy sources. For this to happen, a new wave of technology is desperately needed: one that provides investors with a much more certain return and end users with a shorter payback period for their investment; which will be achieved through low cost, but also highly efficient PV solutions.

There is no shortage of companies who have been willing to gamble on which of the up and coming technologies will be the one to provide this revolution.

ClearViewIP expects that with so many parallel technologies being backed, the IP owners of the winning technologies will seek to ensure market dominance; but perhaps their IP positions will be leveraged to ensure a positive outcome.

© 2013 Angel Business Communications.

Permission required.